I found this link to my old employer on one of our many local housing blogs this morning. It's an old piece on the high wages paid by Trader Joe's, Costco and a handful of other outlets. The text in the link: "A not-so-subtle message for Wal-Mart: Big retailers can pay decent wages and thrive. [Atlantic]" Here's a clip from the article:

The average American cashier makes $20,230 a year, a salary that in a single-earner household would leave a family of four living under the poverty line. But if he works the cash registers at QuikTrip, it's an entirely different story. The convenience-store and gas-station chain offers entry-level employees an annual salary of around $40,000, plus benefits. Those high wages didn't stop QuikTrip from prospering in a hostile economic climate. While other low-cost retailers spent the recession laying off staff and shuttering stores, QuikTrip expanded to its current 645 locations across 11 states.

Many employers believe that one of the best ways to raise their profit margin is to cut labor costs. But companies like QuikTrip, the grocery-store chain Trader Joe's, and Costco Wholesale are proving that the decision to offer low wages is a choice, not an economic necessity. All three are low-cost retailers, a sector that is traditionally known for relying on part-time, low-paid employees. Yet these companies have all found that the act of valuing workers can pay off in the form of increased sales and productivity. Wal-Mart is trying to move into Washington, a move that said local housing blog has not enthusiastically supported. Hence, we've been treated to a lot of impassioned reheatings of that old standby: "Costco shows it's possible" for Wal-Mart to pay much higher wages. The addition of Trader Joe's and QuikTrip is moderately novel, but basically it's the same argument: Costco/Trader Joe's/QuikTrip pays higher wages than Wal-Mart; C/TJ/QT have not gone out of business; ergo, Wal-Mart could pay the same wages that they do, and still prosper.

Obviously at some level, this is a true but trivial insight: Wal-Mart could pay a cent more an hour without going out of business. But is it true in the way that it's meant -- that Wal-Mart could increase its wages by 50 percent and still prosper?

I wrote about this last spring in regard to Wal-Mart and Costco. Upper-middle-class people who live in urban areas -- which is to say, the sort of people who tend to write about the wage differential between the two stores -- tend to think of them as close substitutes, because they're both giant stores where you occasionally go to buy something more cheaply than you can in a neighborhood grocery or hardware store. However, for most of Wal-Mart's customer base, that's where the resemblance ends. Costco really is a store where affluent, high-socioeconomic status households occasionally buy huge quantities of goods on the cheap: That's Costco's business strategy (which is why its stores are pretty much found in affluent near-in suburbs). Wal-Mart, however, is mostly a store where low-income people do their everyday shopping.

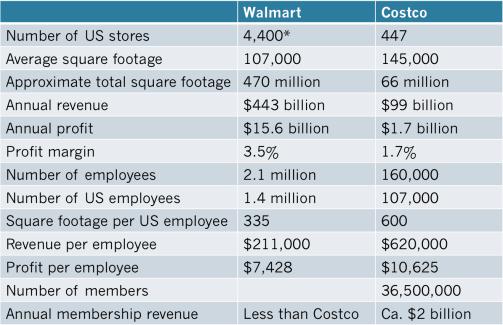

As it happens, that matters a lot. I produced the following graphic to sum up the differences that these two strategies produce:

(*WALMART FIGURES INCLUDE SAM’S CLUB, WHICH DESPITE HAVING MORE STORES, IS MUCH LESS PROFITABLE THAN COSTCO.)

What do you see? Costco has a tiny number of SKUs in a huge store -- and consequently, has half as many employees per square foot of store. Their model is less labor intensive, which is to say, it has higher labor productivity. Which makes it unsurprising that they pay their employees more.

But what about QuikTrip and Trader Joe's? I'm going to leave QuikTrip out of it, for two reasons: first, because they're a private company without that much data, and second, because I'm not so sure about that statistic. QuikTrip's website indicates a starting salary for a part-time clerk in Atlanta of $8.50 an hour, which is not all that different from what Wal-Mart pays its workforce. That $40,000 figure is for an assistant manager, and seems to include mandatory overtime. To this let's add a third reason: QuikTrip is a convenience store, a business that bears minimal resemblance to a department store, the category into which Wal-Mart falls. I mean, yes, you can buy candy at both places, but you can also buy a candy bar at the movie theater, and I still wouldn't head to my local Wal-Mart for a 3:30 p.m. showing of "The Butler."

Trader Joe's is also private, but we do know some stuff about it, like its revenue per-square foot (about $1,750, or 75 percent higher than Wal-Mart's), the number of SKUs it carries (about 4,000, or the same as Costco, with 80 percent of its products being private label Trader Joe's brand), and its demographics (college-educated, affluent, and older). "Within a 15-minute driving radius of a potential site," one expert told a forlorn Savannah journalist, "there must be at least 36,000 people with four-year college degrees who have a median age of 44 and earn a combined household income of $64K a year." Costco is similar, but with an even higher household income -- the average Costco household makes more than $80,000 a year.

In other words, Trader Joe's and Costco are the specialty grocer and warehouse club for an affluent, educated college demographic. They woo this crowd with a stripped-down array of high quality stock-keeping units, and high-quality customer service. The high wages produce the high levels of customer service, and the small number of products are what allow them to pay the high wages. Fewer products to handle (and restock) lowers the labor intensity of your operation. In the case of Trader Joe's, it also dramatically decreases the amount of space you need for your supermarket ... which in turn is why their revenue per square foot is so high. (Costco solves this problem by leaving the stuff on pallets, so that you can be your own stockboy).

Both these strategies work in part because very few people expect to do all their shopping at Trader Joe's, and no one expects to do all their shopping at Costco. They don't need to be comprehensive. Supermarkets, and Wal-Mart, have to devote a lot of shelf space, and labor, to products that don't turn over that often.

Wal-Mart's customers expect a very broad array of goods, because they're a department store, not a specialty retailer; lots of people rely on Wal-Mart for their regular weekly shopping. The retailer has tried to cut the number of SKUs it carries, but ended up having to put them back, because it cost them in complaints, and sales. That means more labor, and lower profits per square foot. It also means that when you ask a clerk where something is, he's likely to have no idea, because no person could master 108,000 SKUs. Even if Wal-Mart did pay a higher wage, you wouldn't get the kind of easy, effortless service that you do at Trader Joe's because the business models are just too different. If your business model inherently requires a lot of low-skill labor, efficiency wages don't necessarily make financial sense.

That's not the only reason that the Trader Joe's/Costco model wouldn't work for Wal-Mart. For one thing, it's no accident that the high-wage favorites cited by activists tend to serve the affluent; lower income households can't afford to pay extra for top-notch service. If it really matters to you whether you pay 50 cents a loaf less for generic bread, you're not going to go to the specialty store where the organic produce is super-cheap and the clerk gave a cookie to your kid. Every time I write about Wal-Mart (or McDonald's, or [insert store here]), several people will e-mail, or tweet, or come into the comments to say they'd be happy to pay 25 percent more for their Big Mac or their Wal-Mart goods if it means that the workers are well paid. I have taken to asking them how often they go to Wal-Mart or McDonald's. So far, no one has reported going as often as once a week; the modal answer is a sudden disappearance from the conversation. If I had to guess, I'd estimate that most of the people making such statements go to Wal-Mart or McDonald's only on road trips.

However, there are people for whom the McDonald's Dollar Menu is a bit of a splurge, and Wal-Mart's prices mean an extra pair of shoes for the kids. Those people might theoretically favor high wages, but they do not act on those beliefs -- just witness last Thanksgiving's union action against Wal-Mart, which featured indifferent crowds streaming past a handful of activists, most of whom did not actually work for Wal-Mart.

If you want Wal-Mart to have a labor force like Trader Joe's and Costco, you probably want them to have a business model like Trader Joe's and Costco -- which is to say that you want them to have a customer demographic like Trader Joe's and Costco. Obviously if you belong to that demographic -- which is to say, if you're a policy analyst, or a magazine writer -- then this sounds like a splendid idea. To Wal-Mart's actual customer base, however, it might sound like "take your business somewhere else."

This is not actually just a piece on how Wal-Mart can only pay low wages -- I don't know how much more they could afford to pay before they started to lose customers (or the board kicked the CEO out), and neither does anyone else writing about this. I'm actually interested in the larger point: the way that things most people rarely think about -- like the number of products that a store carries -- have far-reaching effects on everything from labor, to location, to customer service and demographics. We tend to look at the most politically salient features of the stores where we shop: their size, their location, the wages that we pay. But these operations are not so simple. They are incredibly complex machines, and you can no more change one simple feature than you can pull out your car's fuel injection system and replace it with the carburetor from a 1964 Bonneville.